Boosting Energy with Traditional Chinese Medicine

Qi: The Vital Life Force

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) views Qi (pronounced chee) as the essential energy that sustains all life. This isn't merely a philosophical idea - it's the tangible force that powers every cellular process, from organ function to emotional regulation. When Qi flows freely, we experience vitality; when blocked, we face discomfort and disease. Picture it as the electrical current running through your body's circuitry, invisible yet indispensable for operation.

While often compared to breath, Qi transcends simple air movement. It's the animating spark that differentiates living beings from inanimate objects. Ancient texts describe it as the bridge between physical form and cosmic energy. Modern practitioners observe its effects through measurable changes in patients' health when Qi circulation improves. The subtle pulse variations acupuncturists detect demonstrate Qi's real physiological impact.

The Channels of Energy Flow: Meridians

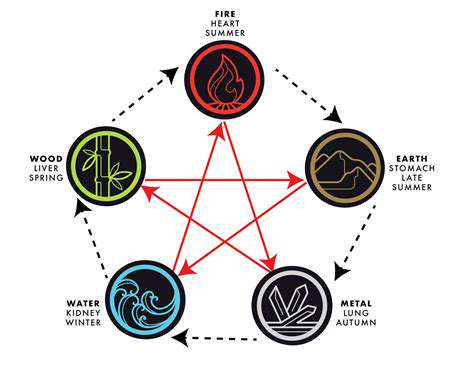

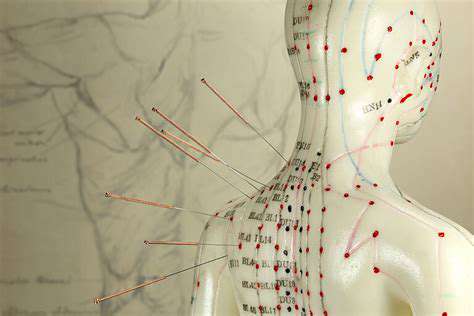

The body's meridian system functions like an intricate highway network for Qi transportation. These 12 primary pathways connect surface acupuncture points to internal organs in specific patterns. For instance, the Lung meridian begins near the collarbone and runs down the arm to the thumb, influencing respiratory health. Research using thermal imaging shows temperature changes along meridian lines during acupuncture, supporting their physiological reality.

Each meridian has peak activity times according to the Chinese body clock. The Stomach meridian peaks at 7-9 AM, explaining why breakfast significantly impacts energy levels. Understanding these rhythms allows for targeted interventions - massaging Pericardium meridian points during its active period (7-9 PM) may enhance sleep quality.

The Importance of Balance: Yin and Yang

Yin and Yang represent complementary opposites governing all natural processes. In the body, Yang corresponds to metabolic activity while Yin relates to structural nourishment. A simple diagnostic indicator: Yang deficiency often causes cold intolerance, while Yin deficiency leads to night sweats. The ideal state isn't equal amounts but dynamic equilibrium - like a dancer maintaining perfect balance while constantly moving.

Factors Affecting Qi Flow

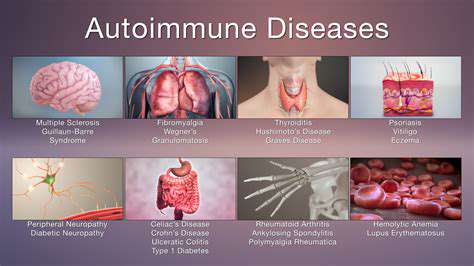

Modern stressors uniquely disrupt Qi. Chronic screen use strains the Liver meridian (eyes connect to Liver in TCM), while sedentary lifestyles cause Qi stagnation in the legs. Environmental toxins create what TCM calls damp heat - a congestion pattern manifesting as inflammation. Even emotional repression (common in Western cultures) leads to stuck Qi, potentially contributing to conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

Restoring Qi Balance Through TCM Practices

Contemporary adaptations of ancient practices show promise in clinical studies. Electro-acupuncture (using mild electrical stimulation) enhances Qi flow for pain management. Medical Qigong protocols help cancer patients manage fatigue. Herbal formulas like Xiao Yao San (Free and Easy Wanderer) demonstrate anxiolytic effects in research, validating their traditional use for smoothing Qi stagnation related to stress.

The Role of Diet and Lifestyle in Supporting Qi

TCM nutrition emphasizes food energetics - how ingredients affect Qi beyond just nutrients. For example, walnuts (warming Yang) benefit cold constitution individuals, while mint (cooling) helps those with excess heat. The practice of food combining - like pairing ginger (dispersing) with shellfish (cold) - exemplifies sophisticated Qi-balancing strategies Western nutrition overlooks.

Dietary Strategies for Boosting Qi and Energy

Understanding the Concept of Qi

Modern interpretations liken Qi to mitochondrial function - the cellular energy production that directly influences vitality. Research shows Qigong practice increases ATP production, providing a scientific basis for Qi's energizing effects. This bridges ancient wisdom with current biochemistry, showing how dietary support for Qi parallels nutritional strategies for mitochondrial health.

The Role of Diet in Qi Balance

TCM's dietary principles anticipate modern nutritional science. The emphasis on cooked foods (easier to digest) aligns with current understanding of gut microbiome needs. Bitter foods (dandelion greens, citrus peel) recommended for Liver Qi stagnation contain compounds that support phase II liver detoxification. This synergy between ancient observation and modern science validates TCM's dietary approach.

The Importance of Fresh Foods

Seasonal eating in TCM corresponds to nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Spring greens contain bitter compounds that stimulate Liver Qi after winter's heaviness. Autumn root vegetables build Yin for winter. Studies confirm seasonal produce has higher phytonutrient levels than out-of-season counterparts, showing the wisdom of this approach.

Nourishing Qi with Specific Foods

Modern research validates many TCM food classifications. Ginger (a warming Qi mover) contains gingerols that enhance circulation. Goji berries (nourish Liver and Kidney Qi) rank among the highest ORAC (antioxidant) foods. Functional MRI studies show certain spices literally warm the brain's temperature regulation centers, explaining their traditional classifications.

Avoiding Foods That Dampen Qi

TCM's warnings about damp-forming foods (dairy, processed sugars) correlate with modern understanding of inflammatory and microbiome-disrupting effects. The recommendation to limit raw foods for those with Spleen Qi deficiency parallels findings about zonulin production and gut permeability in sensitive individuals.

The Influence of Seasonality on Qi

Circannual rhythms in gene expression (like winter increases in fat metabolism genes) validate TCM's seasonal recommendations. Eating with these biological rhythms - lighter in summer, more nourishing in winter - optimizes metabolic efficiency. This chrono-nutrition approach is gaining recognition in Western functional medicine.

Beyond Food: Lifestyle Factors for Qi Enhancement

The TCM concept of Shen (mind-spirit) regulation through meditation finds support in neuroplasticity research. Studies on forest bathing (a Qi-enhancing practice) show measurable increases in NK cell activity. These findings validate the holistic TCM approach linking environment, activity, and dietary strategies for optimal Qi flow.